More history of more languages you’ll

never learn…

A fancy word that’s relatively easy to spell? Masochism. I guess you know what it means. And yet, here you are, ready for a second serving of random facts on language history, politics and orthography. You have (presumably) had a look at, maybe even finished, an article entitled “Playwright, conscience … fish?” in eMAG #34. Amazing details about Korean writing and the evolution of Modern Greek have been revealed to you. What’s next, you ask? More irrelevant facts! And prepare for puns, as well.

Hanoi’ing spelling habits? Thank the

French.

Remember how Koreans had to use Chinese characters before they developed their own alphabet? How, just to write down the most basic things, they were forced to learn the writing system of a completely unrelated language (I know they’re geographically close, but no relation between Korean and the Chinese languages has been proven so far)? Vietnamese speakers, whose language is equally unrelated to Chinese, and whose country is equally close to China, had similar problems. Unlike the Koreans, the Vietnamese had some success in adapting Chinese characters to Vietnamese, to a point where they were illegible even for Chinese speakers. This script, Chữ Nôm, was the first real Vietnamese writing system. It was used for administrative purposes at first, but later on, even poetry would be written in Chữ Nôm. But that doesn’t solve the problem that Chinese characters, a very reduced form of writing, can’t illustrate grammatically important changes within a word.

The most modern

form of Vietnamese writing came from a complete outsider, the Jesuit monk and

missionary Alexandre de Rhodes. De Rhodes, who came from the French-speaking

region of Avignon, created an adapted version of the Latin alphabet that could

reflect the pronunciation of Vietnamese words better than Chinese characters

could. He did take over a few rather inefficient French spelling habits, e.g.

<ph> to express the f-sound, so the system still contains some traces of

other languages. In general, however, it is a neat writing system that has

survived since the 16th century, throughout all kinds of political

regimes, occupations and the division of the country. For this reason, despite

his colonialist background, the Vietnamese still look somewhat fondly at de

Rhodes.

There’s

Norway around spelling rules.

Why don’t we

have a look at Norwegian next? We’ll see a language whose main writing system, Bokmål

(book tongue), is essentially Danish with slight changes. Danish and Norwegian

are very closely related and can be intercomprehensible, depending on what

dialect speakers use. The language similarities and parallels in writing come

in handy today, but they stem from the long Danish domination of Norway. The

two states were seen as one country well into the 19th century. For

this reason, Bokmål still is the dominant writing system, although Nynorsk

(New Norse, ironically the older writing system), fits Norwegian pronunciation

patterns better. The further you move west (away from Denmark), the more

popular Nynorsk gets.

Both varieties

are officially recognised by the Norwegian state, taught in the same schools

and used in public to various extents. Members of the administration are

expected to reply to mail in the same variety that was used in the request and

no province is allowed to use one variety to more than 75% in official areas.

Since Danish and Swedish are also allowed in official written correspondence,

the system can appear quite chaotic. And we’re not even counting in the more

antiquated varieties Riksmål (national language) and Høgnorsk

(High Norse). These former writing standards (with Riksmål being even closer to Danish

and Høgnorsk being even further

from it) have thankfully become rare, but there are people and organisations

willing to invest a lot of time, just to keep them somewhat alive. Is that a

lot to take in? It gets even weirder when you take into account that less than

six million people speak Norwegian at all.

In the area of

writing, Norway hasn’t distanced itself from Denmark as much as Korea or

Vietnam have from China. That’s because Danish rule over Norway ended very

late, both languages were related to begin with and the relations between both

nations are friendly today. The outcome, however, is kind of problematic:

people need to be fluent in both systems and people artificially switch between

two idioms just to fulfil a legal quota. However, no one is discriminated

against based on how they write, and that’s still a nice thing.

I Afri-can’t

spell that!

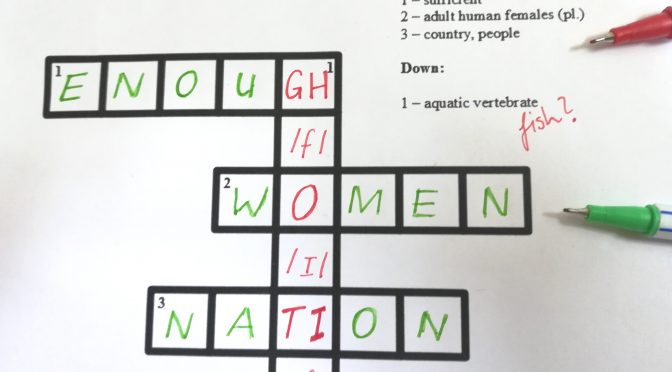

No list of inefficient writing systems

could be complete without the African continent. Most African languages simply

weren’t used in writing before European colonisation. When writing systems were

created, they were based on European languages, mostly English and French. They

also weren’t made up by linguists, but usually by missionaries trying to

translate the bible (who would just work with what they were used to). Now,

English and French are both kind of inefficient in their writing, since both

preserve a spelling that is out of sync with modern pronunciation. Just think

of fish = ghoti or the French city of Bordeaux using four letters to

express one o-sound. French uses <ou> (two letters) for a simple u-sound,

and the more efficient, single letter <u> for the somewhat fancy u-Umlaut

(<ü> in German or Turkish) – a sound few languages use at all. English,

on the other hand, simply doesn’t have a long e-sound. And of course, these

inefficiencies were taken over into new languages by means of their spelling.

Using the Latin alphabet for African

languages can only work out when it is a neutral form where the pronunciation

of certain letters is not tied to their pronunciation in one specific Western

language. On top of that, additional sounds should be expressed through accents

or additional characters, rather than ever-longer combination of letters. For

this reason, the German Ethnologist Diedrich Westermann developed the Africa

Alphabet and presented it (to colonialists, not Africans) in London in

1928. The alphabet has been adjusted to the linguistic situation in (Western)

Africa several times and now has close to sixty letters. That may sound like a

lot, but since you wouldn’t need all of these in every language, learning the

alphabet wouldn’t even be such a big deal.

The real problem

is that Africans aren’t using this alphabet to the extent that linguists have

been hoping for. That’s because many native African languages are used in more

private, oral settings. And when private communication is in written form, e.g.

when people are chatting, most African languages aren’t available (e.g. as

auto-correct on cellphones or as spell-checks on a PC). The ones that are

available, like isiZulu or Somaali, don’t use the Africa Alphabet as a starting

point. And even in handwriting, few people are aware of its existence, since

most African states don’t do a lot to promote a standardized use of native

languages – there are just too many, and most governments have different

priorities. Still, the alphabet is around and offers a good starting point to

any attempt of standardisation. Although it was established through

colonisation, it can be a means of self-empowerment that makes local African

languages and cultures more independent, giving them a stable, written

foundation.

So yeah, the struggle with spelling is real, for a lot of people. Languages influence each other, and they don’t always copy each other’s most positive aspects. If we all looked at languages neutrally, leaving aside history, customs and patriotism (like former Yugoslvia did, for instance), we could probably create a couple of pretty logical writing systems and solve a huge lot of problems. But how likely is that?

Author and picture: Niklas Schmid